Lost, Trapped, Rescued

- Derek May

- Dec 14, 2021

- 23 min read

By John Fiske Burg:

A few weeks ago, my mother-in-law forwarded me an email about her cousin's recent harrowing experience of being lost and trapped alone for five days and four nights in Zion National Park. Reading John Burg's story, there were so many elements that struck me. The story of mental and physical fortitude necessary to have endured such a trauma, the heroism displayed by family, friends, and rescuers during the search, and the lessons we can all take away (and hopefully apply) from reading the account. But I think the most amazing aspect is that John, in fact, lived to tell this tale. As you can read, it could have ended very differently at any point. But the happy ending allows us to experience the event under the unique circumstances of two perspectives—through the eyes of both the rescued and the rescuers. Such is, unfortunately, not always the case.

To set the stage and its players, here's a little rundown. John Burg is a 79-year-old retired city planner. He and his wife, Soraya, love in Glenwood Springs, CO. John grew up hiking and skiing in Colorado and is an active member of the 100 Club, a group of avid hikers. His son, Lee, lives in Minneapolis, and his daughter, Bahar, lives in Denver.

Below you'll find both John's and Bahar's emotional accounts of this incredible experience.

—Derek May (FP Editor in Chief)

Intent

My intent here is primarily therapeutic, an attempt to deal with my trauma of being lost in Zion’s wilderness for five days and four nights; also, in sharing this experience, to possibly provide insight for others. Given the deterioration of my body and mind during this trauma, my memories are no doubt faulty—at times even hallucinations.

DAY 1 – Tuesday, September 28, 2021

We 100 Club hikers are gathering in a Kanab, Utah, hotel lobby to eat breakfast and informally chat about the day's hikes: who’s going where, with whom. Over the past weekend I’d reviewed Gerry Roehm’s online blog regarding the week’s offerings. I’d planned to make a light day of it, hiking in the morning then driving up to the small village of Duck Creek to scout out the place for a family gathering in the spring. The blog, along with the casual reading of other online sites, left me with the impression that I might fairly easily do one or more of the hikes near Canyon Overlook on the park’s east side. I had the impression that the Temple Loop hike was not that hard and that there were cairns to follow on the return side of the loop. Though two people expressed mild interest, I felt they preferred to hike more than take the drive to Duck Creek, so I was on my own, which I didn’t mind.

I returned to my room, pulled the Temple Loop hike map from my packet, filled my pack’s bladder, threw in a sandwich, and headed out. As I entered Zion, the sun was low in the sky and the views from the car were spectacular. I took a few photos from the car to share with Soraya and her two sisters who would see this all in the spring. As I approached the east end of the tunnel, I saw that the parking area was full, but a few young women returning from Canyon Overlook saw me and said I could have their spot. A good omen.

The path to, and Canyon Overlook itself, were wonderful. Breathtaking vistas in all directions. No wonder it attracts visitors by the thousands. The slick rock mountain and Temple Rock to the north were alluring. I’d hiked Boulder Mail Trail’s slick rock in Grand Escalante in the past—blistering hot on that day with a survival story of its own—but this morning was cool and refreshing. Seductive. I felt a great sense of exhilaration and adventure as I slowly picked my way back and forth up its challenging pitch. I stopped often to photograph the beautiful foreground stone and canyons and immense magnificent mountains.

Before long, I reached the saddle and took in Temple Rock to the west, the bowl to the north, Shelf Canyon at its edge, and a vast array of mountains to the northwest. The drop into the bowl was steep, but before long I found footprints that led me down. At the edge of Shelf Canyon, I saw what I thought was a cairn. When I got close, I discovered it was a small hoodoo at the edge of a sheer drop into the canyon; no apparent path. I backtracked—one of many—in search of the route. I viewed my map, put it in my front pocket, and noticed and followed a horizontal striation that led to, then followed along, Shelf Canyon’s rim. This semblance of a trail with occasional footprints lead to a dead end. No apparent way to go.

As I sat thinking, I noticed footprints in the sand leading down a steep bank beneath very low-hanging branches. Thinking maybe this is it, I followed them down to a cliff. Very difficult coming back up. I sat puzzled. I didn’t want to go all the way back, especially with the prospect of descending the steep, slip rock. As a last resort, I climbed a short nob I was beneath and discovered footprints on top. My map had slipped out of my pocket. My aged GPS, with its scratched screen, was of little use, but I remembered from the map that the trail followed a ridge and here in front of me was a ridge and a few animal and human footprints.

The ridge ran into a cliff, so I searched for a way down to a drainage to my left. I eventually found a potential route that involved picking my way through a rocky edge, then to slick rock that looked to be gradual at its beginning but too steep as it approached the bottom. I thought I could possibly do a controlled butt slide through this final steep descent. All went reasonably well until I began the butt slide. As I accelerated, my feet grabbed the rock and flipped me head first downward. The crash was sudden and painful. Significant cuts and bruises, but surprisingly no broken bones. It could easily have killed me. I was grateful to be able to carry on downward through the bottom of the drainage. Again I was confronted with a near identical situation, a steep decline into doable slick rock with a butt slide at the end—and again a similar result, a crashing flip forward.

I followed the drainage until it came to a large, impassable pour off, so I began my trek around to its left, bushwhacking through a partially forested area. How far should I go to get around? Suddenly, it became too dark to see, so I simply stopped and curled up for the night. I thought perhaps I should eat my sandwich, but as I took the first bite, I couldn’t swallow. I had run out of water much earlier and my throat was parched.

A surreal night. I was first dazzled by the clarity of the stars. Clouds rolled in. There were reflections of a canyon wall from distant lightning. Light darkness and shadows all became abstract, making it impossible to discern reality. Lightning overhead was followed by a light rain. I saw folks carrying bobbling lanterns coming to rescue me and glowing animals eyes making their way down canyon walls. Very real, though in time, I realized they were stars. I was sleeping on an uncomfortable slope, so I managed to scoot my way slightly upward with my back against a protruding tree root.

DAY 2 – Wednesday, September 29

I was anxious to get on my way as soon as I could see. More bushwhacking downward until I came upon a bluff with a view down several hundred feet to a settlement. I imagined hiking down, then perhaps hitchhiking back to the main road. The end seemed in sight. I traversed the bluff from one side to another only to see sheer cliffs its entire length. I again backtracked and came across a few footprints. These led to the edge of a canyon and what appeared to be a path. There was a green ribbon around a tree at the canyon’s rim, which reinforced my view that this may be the way down. Looking over the edge, it seemed doubtful, but I had been in situations before where paths existed where they first were invisible.

I followed the path. It led down a ledge with sharp switchbacks, then a spot where I was required to jump a few feet down to a lower sandy ledge. Another ledge with a switchback that led to a downward slanting ledge. The final pitch was a short slide over the final rounded surface into the crevice at the bottom where I could assess the situation. I looked downward. It was dire. The crevice led in a few feet to a 100-foot drop. Upward from me in the crevice was a red strap with a carabiner tied around a rock for rappelling.

There was now no way down and no way up. I was sunk. My life now was totally dependent on being found and rescued.

My habitable spot consisted of a 5-foot long, V-shaped space. My back on the east slick rock, my legs in the foot-wide trough or slightly up the west side. If I moved my feet south to the left, they were in water. If I moved them north to my right, they were on a short slope that led to the precipice. The slice of water left of my feet was about 20 feet long varying in width up to 16 inches, with a depth up to 8 inches. In front of me, facing west, was the variegated canyon wall from which I'd descended. Behind me was a short, slight, slick rock slope up to a wall with an overhang directly above. The throat of the canyon at the end of the water to my left was a series of vertically slanted shelves that became steeper near their top. The distant view to my right—above the drop off—was a long slot canyon with two spires at its end. I imagined the road at the foot of these spires. A narrow view to the sky. My options for resting were limited. With my back against the slick rock, I could put my feet in the space at the bottom of the crevice or slightly up the facing wall. I could bend my injured knees sliding downward or bend at the waist.

The water saved me. Though stagnant and filled with bugs, I filled my backpack bladder with two liters of water twice a day and used the pack for a pillow and water source.

I checked my cell phone again. The battery was dead from all the photography. My GPS read 13.5+ miles with 2,800’ + total ascent—no doubt from all the backtracking. I hollered for help and could hear its echo from the canyon. I repeated this often, hoping a hiker or someone below or above might hear. I occasionally heard faint noises, which I imagined to be from the road, probably muffling my cries for help.

In the afternoon, my heart jumped as I heard the sound of a helicopter. A bubble helicopter came flying up the canyon toward, then over me. I waved both arms frantically then waited for my rescue, which never came. He apparently never saw me or thought I was out for fun. The afternoon also brought brief sun and black flies, which swarmed over the blood oozing from my injured legs. I didn’t have the energy to keep them away.

Again, a long, cold—in the 40s—night. I was dressed in shorts, a light shirt, and a rain jacket. Lots of shakes, efforts at minimal exercise and movement to keep from freezing.

DAY 3 – Thursday, September 30

The rock face in front of me contained a complex bas relief created by a young family: an old train, a mountain lion, an old pickup truck, corrals filled with bulls and other animals, a small group of sheep, a huge white cat with black eyes on a sofa alongside a woman in a lounger, a Mexican adobe home, a mining operation, a portrait of the couple’s daughter, other easy chairs, a title for it all that morphed into a series of animals. This was all very real. I didn’t realize until two days later that they were merely abstract patterns in the stone.

I began to explore escape routes. The first was up the canyon’s throat beginning at the upper edge of the water. The first part was conceivable, so I gave it a try. The first few feet up the slanted edge were possible, a foot and handhold or two, then nothing but a narrow slot. I thought maybe I could wedge my feet against one side and my back against the other. I tried but could not scoot my back upwards. My back started to slide below my feet. I was perilously close to sliding and bumping headfirst on my back down the rock. I mustered all my strength and managed to get my feet lower, then edged my way down.

My second potential escape route was behind me up the east face. I could barely make it a few feet up the slick rock, then a foot and handhold or two to the point where the rappel strap was fastened around boulders. I untied the strap and used my remaining hiking pole—the first broke in the fall—to get the carabiner up and around a small pine. I then pulled myself up and over this intermediary ledge. It was nice there, sandy and sunny with only a slight slope. I wedged my foot against an outcropping to keep from rolling off and took a short nap. But, climbing above was not possible. Though this spot was more comfortable, it had no water and, with its severe overhang, had minimal view from the sky. I eased my way back down.

As evening approached, I noticed that someone was placing jeeps for advertising on top of the two spires at the far end of my slot canyon. Much work going on there with many workers. I was irritated that the Park Service would allow such a thing but thankful that they were up there with their large helicopter and would soon come to rescue me. Work went on for a long while. Most of the crew had assembled to board their copter, but a few stayed behind to erect and adjust a large wind generator that would light the jeeps. As it evolved, the wind contraption was also being used to inflate large spinnaker sails for advertising. They were being tested in short bursts—poof, poof, poof. This went on until dark, but I reasoned they had only postponed my rescue until morning daylight. They failed to arrive in the morning, and it took me a long while to realize I was hallucinating.

Another frigid, miserable night. My new escape idea during the night was to use my remaining sticky cheese sandwich to coat the bottom of my shoes so that I could have good traction going up the facing canyon wall.

DAY 4 – Friday, October 1

I was becoming very weak and desperate. Though I would periodically holler for help and wave at anything but the highest of planes, I was losing hope for a rescue. I felt my only chance was to somehow get to the bluff and either holler down for help or become more visible.

I remembered that there were a number of loose boulders on the ledge up behind me. Using the rappel strap as before, I made my way up to this shelf and began rolling boulders—from basketball to softball size—over the edge, where they crashed and ended up in my water trough.

I made my way down and moved the boulders to create a large enough carin-like step so that I could mount the west rock face ledge. I cleaned the bottom of my shoes with a small knife but abandoned the sticky cheese idea. I got the rocks high enough, but each time I tried to push off, the stones would tumble, and I’d fall back. I rebuilt the steps several times, then got the idea of lashing them together with the rappel strap. This finally worked, and I was able to sprawl myself over this slanting shelf and scoot like a snake far enough up to stand. I retraced the route of my entry, mentally explored options of going higher. There were none.

I grew despondent. I reviewed my life and my imminent death. I was grateful for the life I had, knowing that at 79 I was approaching my natural life expectancy at any rate. Sad, but I realized that life will go on. I did not want to go through another night. They were so painful. I contemplated ways to peacefully make my body shut down.

Late afternoon, I checked my dead phone one more time, and low and behold there was a glimmer of light. I hit the button for a call to Lee and told his recording that I was alive before it cut out. I called 911. The lady answered and asked where I was. I said in a slot canyon and couldn’t remember anymore—as if I knew. The call and the phone went dead.

But there was a glimmer of hope.

Another nearly unbearable long, cold night.

DAY 5 – Saturday, October 2

Daylight brought increased aircraft, though most seemed far out of view. Whenever I could see one, I would wave my arms. I’d also made a display from my pink role of hiking ribbon to better mark my spot. But nothing. I was very weak.

Afternoon brought the glorious, thundering sound of Black Hawk helicopters—several orders of magnitude above the recreational types. Giant war machines. They made several passes but would disappear, then return. Finally one banked sharply above, then returned on another pass, and a ranger popped his head out and waved.

I wept.

They were out of view above on the bluff. The helicopter’s wind increased, and a shower of sand and debris filled the canyon as the copter descended. I heard my name, “John, we’re going to get you out of here.”

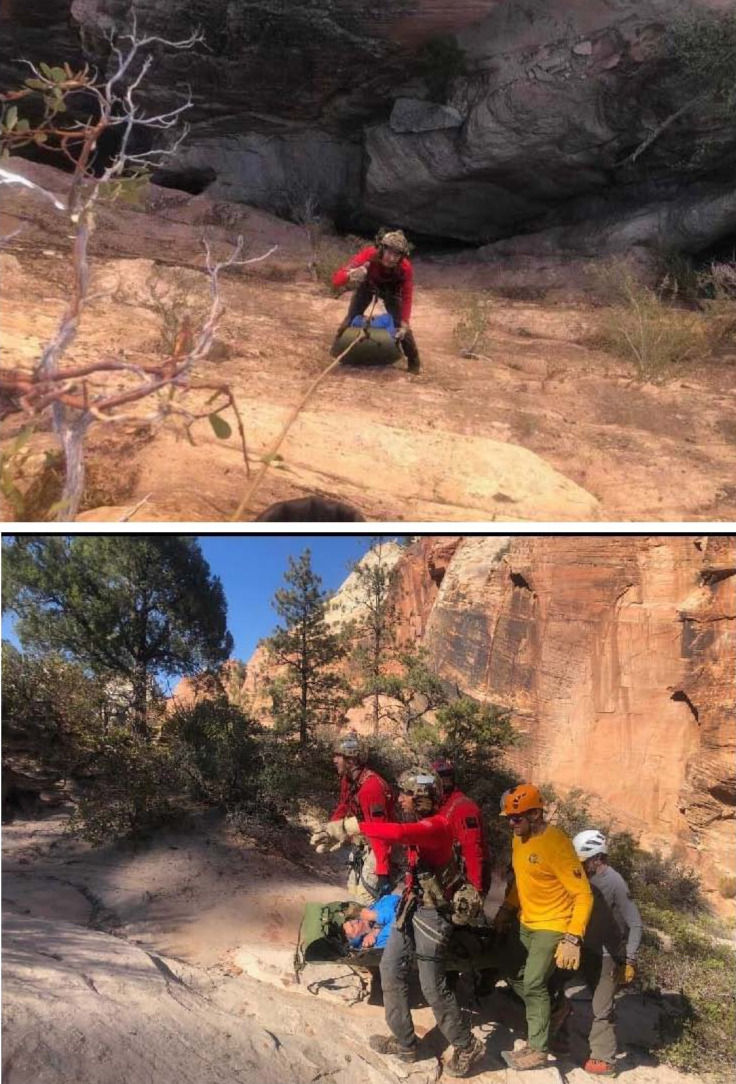

Several of them rappelled down the throat of the canyon. They were young, highly trained professionals. The medic among them, maybe Pat, reached me first and administered basic medical tests on my back, my neck, coherence, vitals, etc. He said that they spotted my blue jacket on their last pass. He and his teammate unrolled a plastic sled-like device in the crevice and carefully strapped me in mummy-like. A long rope was flug over the west wall and attached to the head of my sled and Pat. The team then pulled me and Pat, with his legs on both sides of the sled facing me, up the wall.

On the way up, Pat happily said he could now get his tattoo for his first save.

On top of the bluff, six of the rangers, three on each side, carried me a considerable distance up through the brush to the helicopter landing site. As the Black Hawk then returned, stirring up the huge sandstorm, Pat leaned over and sheltered me from the sand and debris. We lifted off and flew the short distance to St. George Regional Hospital, where I met my family.

Search & Rescue (SAR)

I became aware of the search and rescue operation after the fact through conversations with Soraya, Lee, and Bahar plus copies of news reports. It was far more extensive than I imagined and really kicked into high gear following my Friday cell phone calls to Lee and 911. Many organizations and resources were involved, including Zion National Park SAR Teams, Nellis Air Force Base and the 66th Rescue Squadron, Washington County Sheriff's Office, K-9 Units, Drone Teams, Grand Canyon, and the Zion National Park Services Investigative Services Branch Tip Line. As written on Zion’s social media, “This successful rescue would not have been possible without the network of individuals and resources.”

Wednesday, September 29

I was woken by a phone call from my mom at 6:30 a.m. Half asleep, she says, “Bahar, your dad went hiking in Utah yesterday and didn’t return to the hotel last night.” She was informed at 3:45 a.m. “His phone goes directly to voicemail,” she says. My heart sunk. I asked her the obvious questions: “Who was he with? Where was he planning on going?” Her answers were, “By himself and don’t know.” I could tell my mom was frightened, but she said, “He’s a strong man.” I remember thinking She’s right, but this is bad. My dad had mentioned to us a week or so earlier that he was going to research an area called Duck Creek Village while he was driving through Utah and meeting up with his Colorado hiking club, so that was our first place to search.

My mom began calling the Kane County Sheriff's office to inquire. My initial thought was that he had had a car accident and he drove off a cliff and is either dead or greatly injured. But I also had hope, and I knew we could find him. A body and car cannot vanish instantly. I told my husband, “I’m really scared,” and he replied with, “Me also. Stay positive. He’s a strong man.” That gave me strength.

Around 10 a.m., we were informed that nothing was found at any of the area hospitals. A feeling of sadness, urgency, shock, helplessness, and determination overcame me. I needed to get to Utah and find my dad. I bought a flight to meet my mom in Tucson that evening with the plan to drive to Utah the next morning during daylight. Around 3 p.m., I was informed that two hiking club members found my dad’s car on the east side of Zion National Park at Canyon Overlook Trailhead. Yes! I was so hopeful he would be found in the next 24 hours. I Google imaged Canyon Overlook Trail and saw this photo (right).

Holy crap. I now think he slipped off a cliff taking photos and he’s either dead or injured. His car was parked in a very small and popular parking lot, so we assumed he arrived early in the morning. Also, there are many hiking trails to the north AND south sides of that trailhead. So many possibilities. After a day of crying, trying to stay calm, researching Utah search & rescue information, and work, I head to the airport with hopes that I will have a voicemail after the flight telling me my dad has been found. Nothing. I arrive at my parents' house in Tucson and force myself to sleep for a few hours as I think about my dad sleeping somewhere under a bush or if he’s dead. If he’s alive, this is his second night out there.

Thursday, September 30

I awaken with a split second of peace and then realize this is actually happening. I am waking up to a nightmare. I start bawling. My dad is a rock for me, and I’m not ready to say goodbye. I don’t want my dad to feel any suffering or pain. I know my dad has had a long, fulfilling life, but he has more to offer and enjoy. My mom, aunt, and I leave for southern Utah. I am so grateful my sweet Aunt Minoo drives the entire 9 hours. During the drive, my mom begins receiving phone calls from a Family Liaison Park Ranger named Ben from Zion Search & Rescue. We had poor phone reception and it was difficult to understand what he was saying, but the gist was my dad was still missing, the search was in-progress, but specific plans were unclear.

I’m terrified and frustrated. Every minute counts. This is crazy. Life can change so quickly.

We text more photos of my dad to Ben for the missing person flyers.

We arrive at the hotel in Kanab, Utah, and I immediately find a quiet meeting room where we can call Ben back. He informs us foot searchers and aircraft haven’t found my dad, but they are in the process of engaging more resources—additional aircraft, rappellers, and K-9 dogs. We make plans to meet them on the west side of the park in two hours to discuss details. They ask me to retrieve some of my dad’s dirty clothing for the dogs to smell. I go through his hotel room and get the dirty clothes. I also find a full cooler and mini-fridge of food and several of his warm jackets. My heart sinks again.

My mom, aunt, our close friends Mehrdad and Farshideh, and I make the hour-and-a-half drive to the meeting location. We enter the park area and drive past my dad’s car in awe (above). We meet at some stone houses on the west side of the park as directed by the Ranger team. They lay out a large map on a picnic table, and we discuss search plans. We talk about my dad’s emotional and physical attributes, Tuesday morning and what he may have been wearing, cellphone usage, and his hiking and survival skills.

Driving through the park and reviewing the topographic map makes me frighteningly aware we are dealing with a massive labyrinth. Within a half-mile area of terrain, there are thousands of nooks and crannies. I did gain more hope after physically meeting with the SAR Ranger team and gaining more knowledge of the search plans. I could feel their dedication, expertise, and professionalism (Incident Commander Vance, Kyle Knight, Justin Brearley, and Ben).

We drive back to the hotel and wait. I’m hopeful they will find my dad alive but also preparing myself, my husband, and daughter to not have him with us any longer. If he dies, at least he died doing something he loved. If we never find his body and the birds start eating him, he’d probably think that is cool. Again, I force myself to get some sleep so I have the strength to begin again tomorrow. I envision my dad out there somewhere. I feel awful pulling the fluffy bed covers over me.

Friday, October 1

I’m working off adrenaline. I inquire with the hotel manager about their security video footage so we can determine what my dad was wearing the morning he left. She says the request has been called in and they are examining the video footage. We send more photos to them so he’s easier to spot. I go to my dad’s hotel room to gather all of his belongings and notice some map papers on the desk. I look through them to see if my dad had written any notes. No notes. I find the hiking club leader in the lobby and ask him, “Is this a set of printouts you provided? And if so, is a map missing?” He looks through and indeed a map is missing—it’s of the area where my dad’s car was found and the trails to the north. I immediately text Ranger Ben a photo of it.

The map isn’t very intuitive, and I can see how some people may find it confusing. I feel some hope. Any clue helps at this point. We get frequent updates from Ben about search missions—although every time he calls, we hope for “We found him.” We wait. We make plans to meet the SAR team around 4:45 p.m. to discuss the day’s search efforts. At 4:43 p.m., I receive a text from my brother Lee saying "I love you Bahar. Thank you for being there. I will see you soon." His love and continued optimism is awesome and helps my shattering heart. We arrive at the same stone houses, and this time we go inside and lay the map down with the SAR team. A few minutes into the meeting, around 4:59 p.m., my phone rings. It’s my brother, but the call drops due to limited phone signal. He calls right back, and I run outside of the house for better reception.

My brother says, “Bahar! Dad just called and he’s alive! He left me a voicemail!”

I run into the house and tell everyone. Elation filled the room. I put Lee on speaker, and he immediately texts me the audio message and we confirm it was not a delayed send. We airdrop the message to the SAR team leader’s phone. We listen to it, and his first words are, "Lee. I am alive. . . ." The rest of the message cuts in and out, and very few words are distinguishable as he describes where he is. We look at each other in astonishment. This was good. Very good. The SAR team tells us they’ll listen to the audio message back at their headquarters with specialized equipment to see if they can decipher more words, as well as obtain the cell phone ping. They leave swiftly with determination.

We make the drive back to the hotel, and my mom sees a missed call from my dad at around the same time that my brother received his voicemail. And Ben informs us my dad also connected to 911 around the same time, and they have a similar three-second recording before it cuts out. We take turns listening to Lee’s message using my headphones. Some of us hear the words across, down, leads, opposite, abandoned, place. His location is still very unknown, but we now know he is lost and/or stuck and alive! I rest with a ton of hope tonight.

Saturday, October 2

The morning consists of a lot of investigative work: sending the SAR team GPS radio photos, GPS channel information from the hiking club, Garmin passwords, and hotel video footage of my dad stepping into the elevator at 8:18 Tuesday morning. And the SAR team has directed my brother and I to send a single text message to my dad telling him search and rescue are looking for him and to get to higher ground just in case his phone powers up again. At 11:11 a.m., I receive this text from Ben: "The Black Hawks have 1 hour remaining flight time. There’s also a C-130 airplane that has 4 hours. All of our foot teams are in the field." A 11:55 a.m. text: "Helicopters are going to refuel and will return. We’ll be sending two drone teams to canvas the areas around the Canyon Overlook trail." My mom and I decide she should go to the St. George airport to pick up my brother and keep her phone in range in case my dad attempts to call again. And I will go to the SAR meeting for the daily briefing. I make plans to meet at the stone houses at 2 p.m.

I make the drive and see the two helicopters and C-130 plane zig-zagging through the park. When we arrive at the stone houses, we lay the map out again, and they let me know that the Garmin GPS my dad has on him is an older model that isn’t connected to the Cloud. Also, the cell phone ping isn’t as accurate as we hoped—it’s roughly a 5-mile area, but the single bounces off the mountains. They play the 911 call for me. My dad says, “I’m a missing person. I’m in a slot canyon,” and then it cuts out. I can tell in his voice that he is scared and desperate. My hope drops.

The SAR team proceeds to ask me numerous questions about my dad. Then Justin (the lead investigator) and I separate and look through all of my dad’s belongings for more clues. He keeps asking me questions. He gets a message through his earpiece. I think for a second I should let them go so they can continue the search. More questions.

After a while, Kyle walks over and says, “The Black Hawk just found him and he’s alive. He waved and there are rescuers with him right now. We were stalling so we could confirm and didn’t want to tell you while you were driving on the windy road back.”

I look at him and say, “Is this for real? This isn’t a dream?” I drop to the ground and cry with joy. I give Farshideh a tight, shaky hug. I get into the rangers' truck with their cell phone booster to call my mom. The best call I’ve made, ever. She is ecstatic. The SAR team show me where he was found on the map—at the very north end of the labyrinth. I thank Kyle, Justin, and Ben. I tell them how grateful I am and that they are incredible human beings.

Farshideh and I wait and watch while the two Black Hawks circle around the park. Maybe they are waiting for the rescuers to get my dad ready to be lifted up? They were circling so they could get their fuel levels to the precise level to drop down. After several minutes, they go over the mountain in front of us where my dad is, disappear for a bit, reappear, and then rapidly fly down the canyon toward St. George. They have my dad! We drive to the hospital—the best drive ever. I rush into the ER department and see my dad. He’s rough but joyful looking.

I give him a kiss on the forehead and say, “I love you, Dad. We’ve been looking for you for four nights.” He replies, “I love you, too. I know. I don’t think I would have made it one more night. It’s a miracle. I made so many poor choices out there.”

Reflections:

Life is precious—cherish and nourish your loved ones. Don’t sweat the small stuff—it’s trivial. My mom is so strong. I surprised myself with my strength. I love my brother dearly. My family and friends are an amazing support system. A cellphone is a critical communication and search & rescue tool. My almost 80 year-old dad is a survivor. Enjoy our beautiful Earth but do it safely. The National Park SAR and U.S military are the epitome of kindness and bravery.

Area & Location

(Back to John) Medical Recovery

I spent three days in St. George Regional Hospital, where I received excellent care. A regular round of superb specialists and staff. Along with my superb, highly trained military rescuers, people in the medical and educational fields are also my heroes. This sort of trauma takes a surprisingly huge emotional and mental toll. As I emerged from the hospital, the entire environment seemed totally different. I felt out of touch with the modern world. Everywhere I looked seemed to be crass, in-your-face commercialism. I have increased empathy for those suffering from PTSD, many of whom have experienced far worse than me.

Back Home in Tucson

On Wednesday, October 6, after spending a night in a St. George hotel, we drove to Tucson, a nine-hour drive with Lee driving one car with me and Bahar driving another with Suri. Homecoming here was incredibly welcoming. I began to receive and review many dear messages from family and friends. Among them, a poem from Pat Cima:

For John,

We rejoice in your miraculous rescue dear John,

Our hearts were heavy while you were gone,

Now rest, recover, and be well,

For you have quite a story to tell!

Reflections

My many major faulty judgements are by now quite obvious. Here are a few initial thoughts:

Do adequate research. It’s apparent in hindsight that my research regarding this hike was woefully inadequate. It can be challenging these days with online sources of variable credibility.

Never hike alone. A near absolute, however, perhaps with some qualifications. Solitude with nature has its special quality for many. Perhaps confine alone hikes to those of very low risk.

Notify someone of your plan and changes in plan.

Take appropriate gear. This depends on the severity and risk of the hike. For bushwhacking, this should include the latest technologies for wayfinding, search, and rescue. Of course, adequate water, food, and clothing.

Plan for emergencies. What would happen in the event of serious injury or bad weather?

Manage risks intelligently. This goes for life in general. It’s one thing to risk injury, it’s totally another to risk life itself.

Avoid the sirens’ song. This, in combination with the risk management above. Be aware what risks are involved in pursuing your seductress.

Please consider submitting your work to Flapper Press by contacting us here.

Comments