By Annie Newcomer:

The Flapper Press Poetry Café features the work of poets of all ages from around the globe. This week, we highlight the life and poetry of Brooke Herter James!

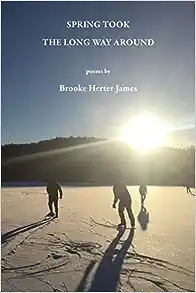

Brooke Herter James lives in a very old house in Vermont with her husband, two donkeys, a mess of chickens, and a dog. She is the author of one children’s picture book, three chapbooks, and one poetry/prose/photography collection. She is the recipient of the 2018 Hunger Mountain's Katherine Paterson Best Picture Book Manuscript Award and has had selected poems appear in PoemTown Vermont, Mountain Troubador Poetry Journal, Orbis, Kansas City Voices, Tulip Tree Review and Rattle as well as the online publications Bloodroot Literary, Poets Reading the News, New Verse News, Flapper Press, Typishly, Writing in a Woman's Voice, and Heartland. She is honored to have been chosen as a finalist in the Poetry Society of Vermont's 2018 National Poetry Contest. Brooke can be found on Facebook (Brooke Herter James) or at brookejamesbooks.com.

Please meet Brooke Herter James!

Annie Newcomer: Welcome to the Flapper Press Poetry Café, Brooke. As I understand after reading about your poetic journey, you won your first creative writing prize in eighth grade but only came back to writing just a few years ago. Did you always know that you would come back to your writing, or did you feel a longing for something lost that you eventually identified as poetry and knew you needed to start writing again?

Brooke Herter James: I had no idea that after all the years of jobs and raising a family were over, writing would reappear in my life. Nor was I entirely surprised. I was raised in a house filled with books and by a mother who loved reading out loud. I grew to recognize the music of words because of her—how often did I hear “Go to the banks of the great grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever trees!” Ten years ago, I began writing picture-book manuscripts, a challenge which soon led me to experiment with poetry. They are often very similar—big feelings expressed in few words. I still work at picture-book writing, but I spend more time with poems.

AN: When we asked you to share a description of your poetry, you responded that your poems are deeply rooted in the quietness of Vermont. So my next question is to ask you to share how "place" affects a poet's writing? If not for Vermont (place), would you have become the same poet you are today? In other words, does "place" drive the poet, or could you have written these poems, or similar ones, in New York City or, say, Paris?

BHJ: My poems most often begin in the very real place in which I live. Would my poetic "voice" be different if I lived in New York City? Yes, I believe it would. I think poets, like grapes, have a terroir. Mine is rural, quiet, hilly, tree-filled, often snow-filled, and everywhere, crisscrossed with dirt roads.

AN: Do you enjoy experimenting with different types of poetry, voices, and subjects, or do you feel you have a distinct voice and pursue only that voice? And why?

BHJ: I am constantly learning about and often experimenting with different poetic forms. As far as subject matter, I am just now trying to stretch beyond the familiar. But I don’t believe a "voice" can be pursued. I think a "voice" is organic and presents itself over time. When I write a poem that is not working, it’s often because I have jammed some alien voice into the poetry. Those poems are best abandoned.

AN: If you could meet any poet whose work you love, who would this be and what question would you ask first?

BHJ: What an impossible question to answer! The poet whose work I love today may take a backseat to another poet tomorrow, depending on what I am looking for in the words. At present, I choose Jane Kenyon. Several of her poems have appeared before me at the very moment I needed them and, in doing so, have taken up residence within me. In addition, I am intrigued by her life with Donald Hall (in a place not unlike my home) and moved by the tragedy of her early death. What question would I ask first? "What do you consider to be your best poem, and (if I am allowed a follow-up) why?"

AN: And yet you answered it. And I love Jane Kenyon's poetry. Her work led me to interview her husband, Donald Hall. I believe I was one of the last to interview him before his death.

Brooke, in the backstory on your poem "While I Wait" (see below), you share that the poem was triggered by the gentleman's slacks, and yet there is no reference to the slacks in the poem. Can you explain how this happens with the creative imagination—an almost sleight of hand in the poet's mind of seeing one thing but it turns out to be a totally different poem when the poet actually sits down to write?

BHJ: The elderly gentleman’s pants reminded me so suddenly and forcefully of my father (no longer living) that I had to step outside the café and sit for a minute with the intimacy of memory. In that moment, I felt a tenderness toward everyone and thing around me—the man’s daughter, the girl, the ceramic dog bowl, the petunias, even the orange-and-white-striped cement mixer. I felt past and present in the late August sun, I felt future in the "you" crossing the street, "waving as you come." This is one of the few times I have been able to let a poem go while I was writing it—to actually watch it shape itself.

AN: Do you set literary goals, and what might some of these be?

BHJ: My current goals are two-fold: to strive for a more disciplined practice of hearing, reading, and writing poetry and to discover an organizing principle for another collection of poems.

AN: What does it take for a poet to feel safely ensconced in the literary world? Or is that feeling of belonging and safety ever even possible?

BHJ: For me, a sense of belonging has everything to do with the feedback I receive from those who have read or heard my poetry. Of course, having poems accepted into journals makes me feel more confident that I am doing some things well. But, truly, the greatest affirmation comes from readers who, out of the blue, reach out to me to say, “I loved your poem!”

AN: What has surprised you the most on your journey through all that is poetic?

BHJ: First, that writing poetry has changed the way I am in the world. I find myself collecting images, pocketing snippets of conversations, writing down words and phrase that intrigue me, saying to myself I must remember this. Often it takes ages for these life "souvenirs" to find their way into a poem, but when they do, I understand precisely why I held on to them.

I have also been surprised and delighted by the community of poets of which I am a part. I belong to two poetry writing groups, both of which sustain me in ways I can’t quite describe. We are generous with one another— by which I mean we read each other’s work with care. I don’t think it takes a village to write a poem, but I do believe it helps to have a handful of trusted poet-friends.

AN: Thank you so much, Brooke, for visiting us in our Flapper Press Poetry Café. Now it is time for me to ask you to share 3 poems and their backstories.

This is a love poem to my husband and the life we live together on a hillside in Vermont. All the characters of my daily existence occupy this poem (except the dog). This is also a poem about creativity in its many forms—the satisfaction of working hard to make something of beauty.

Ars Poetica

He lifts long

planks of wood,

bends them slightly,

tucks their edges,

clamps and glues,

nails and sands,

varnishes and paints

as the moon pauses

on her climb

past the bay

of the barn,

the donkeys linger,

the chickens cluck

and I, on a stool

in the corner,

sit mesmerized⎯

as he coaxes

a seventeen-foot wherry

from a heap of boards.

He, who says he can’t

write a poem.

This poem started with pants. To be more specific, the pants of the elderly gentleman standing ahead of me in line at a nearby coffee shop. They were pressed, khaki dockers—exactly the pants that my father used to wear. I was so overcome with nostalgia I had to step outside where I could sit alone for a moment. But this poem had already found me and wasn’t letting go. The scene I describe is exactly as I lived it, cement mixer and all. The tenderness was triggered by those pants.

While I Wait

At the sidewalk café

a white-haired man

asks for coffee, hot,

cream, no sugar.

His daughter touches his sleeve

and points ⎯ the cranberry scones

in the glass case ⎯

your favorite, remember?

His granddaughter splashes

in the ceramic dog bowl

brimming with cool water

on the porch step

where I sit shielding my eyes

from the sun with a menu,

the salmon pink impatiens

in the clay pots tremble

when a concrete mixer rumbles by,

spinning its vanilla and orange striped drum.

Look, I whisper to the little girl,

a swirled ice cream cone on wheels.

Late August drifts by,

settles on my sun-warmed knees.

A friend of mine died

last week, I say to no one

as I wait for you to cross the street,

waving as you come.

Several years ago, I was asked to write an ekphrastic piece about a fried egg. How could one not write a happy poem about a fried egg? I thoroughly enjoyed getting inside the head (or yolk) of this egg and the life of the diner—the everyday rituals of coffee, breakfast, even the flirtation across the counter. Who doesn’t know this story?! This poem made me happy as I wrote it; it makes me happy each time I read it.

Sunnyside Up at the Sunrise Café

Oh, to be the fried egg

on the blue plate

sliding down the counter

with my sunny side up,

me and my home fry friends,

maybe my buddy toast

all buttered on one side,

Marilyn and Elvis winking down

from over the pass-through

as I come to a perfect stop

in front of you.

You’ve got the daily news

opened on your right,

knife and fork on your left &

you say, Hey, Dolores, how about some Joe?

& she fills you right up to the brim.

I know it’s not much,

but it’s not nothing either,

to be part of that story,

to be there at the start

of each day—when you say

You’re a good egg, Dolores,

I should have married you

when I had the chance,

and she laughs

her beautiful laugh.

Annie Klier Newcomer founded a not-for-profit, Kansas City Spirit, that served children in metropolitan Kansas for a decade. Annie volunteers in chess and poetry after-school programs in Kansas City, Missouri. She and her husband, David, and the staff of the Overland Park Arboretum & Botanical Gardens are working to develop The Emily Dickinson Garden in hopes of bringing art and poetry educational programs to their community. Annie helms the Flapper Press Poetry Café—dedicated to celebrating poets from around the world and to encouraging everyone to both read and write poetry!

If you enjoyed this Flash Poet interview, we invite you to explore more here!

Presenting a wide range of poetry with a mission to promote a love and understanding of poetry for all. We welcome submissions for compelling poetry and look forward to publishing and supporting your creative endeavors. Submissions may also be considered for the Pushcart Prize.

Comments