A Shared Universe of Doom: The Lovecraft Circle and the Cthulhu Mythos

- John C. Alsedek

- Nov 27, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 3, 2022

By John C. Alsedek:

That the late H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937) was one of the most influential horror writers in the history of the genre is beyond question; John Carpenter, Guillermo del Toro, Neil Gaiman, and Stephen King are among the luminaries who cite Lovecraft as having a huge impact on them. Though Lovecraft died relatively young and almost penniless, he left behind a literary masterpiece known as the "Cthulhu Mythos," a fictional universe named for his most famous creation, the brain-shattering alien horror known as Cthulhu.

In it, humans exist in an uncaring universe inhabited by monstrous entities of almost limitless power, and to even learn of their existence is to invite madness . . . or fates far, far worse. It is best summarized by the first line from "The Call of Cthulhu," which was first published in 1928:

“The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.”

But while Lovecraft originated the character Cthulhu, the Cthulhu Mythos was a shared universe; and that was by design, for he invited all his literary friends to add to it. This is what became known as "The Lovecraft Circle," and it included some of the greatest writers of speculative fiction to emerge from the 20th century, including Robert Bloch, Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber, Frank Belknap Long, Clark Ashton Smith, Donald Wandrei, and the previously discussed Henry Kuttner & C. L. Moore.

As a person, Lovecraft had some faults that are glaringly obvious today; in particular, the racism and xenophobia exhibited in his earlier works stand out as abhorrent. But at the same time, he was a product of both his time and his upbringing, and one can look at his later writings and see a distinct shift in those feelings as he got out into the world and met people different from himself. Lovecraft also has this reputation of being a recluse, but in fact he genuinely enjoyed traveling (limited more by his means than his desire), and he was an avid correspondent who went above and beyond to encourage and assist aspiring writers. So, it makes sense that he actively encouraged others to make their own contributions to the Cthulhu Mythos.

And make contributions they did, with Lovecraft’s Weird Tales comrades Clark Ashton Smith and Robert E. Howard at the forefront early on. A talented poet, painter, and sculptor in addition to being a writer, Smith added such characters as the Old One Tsathoggua and the wizard Eibon to the Mythos, as well as tying his Hyperborean pre-history stories into it. And Howard not only linked his Conan the Barbarian tales to the Mythos but also wrote a number of short stories that incorporated elements of the Cthulhu Mythos, including an absolute classic tale of horror in "The Black Stone." Young Robert Bloch chipped in with a bunch of stories and two mystical tomes that would become commonplace in the Mythos: "De Vermis Mysteriis" and "Cultes des Goules." Frank Belknap Long contributed such memorable monstrosities as the Old One Chaugnar Faugn and the Hounds of Tindalos, a pack of malevolent alien horrors that dwelled in the angles of space and time.

The contributions weren’t just one-way either, as Lovecraft playfully referenced the works of his friends (and sometimes his friends themselves) in his own works. When Howard had his character Friedrich Von Junzt read Lovecraft’s dread fictional tome the Necronomicon in "The Children of the Night," Lovecraft reciprocated by mentioning Howard’s equivalent ancient tome, Unassprechlichen Kulten, in two stories. Lovecraft’s short story "The Whisperer in Darkness" mentions the Atlantean high priest Klarkash-Ton (a jokey nod to Clark Ashton Smith). And when Robert Bloch killed off a character modeled on Lovecraft in his "The Shambler from the Stars," Lovecraft returned the favor by making a thinly veiled version of Bloch the protagonist of "The Haunter of the Dark" . . . and then having him meet a most unpleasant end.

After Lovecraft’s death in 1937, another member of the Lovecraft Circle, August Derleth, essentially took over stewardship of Lovecraft’s literature and of the Cthulhu Mythos. In general, this was a positive development, as Derleth not only kept interest in Lovecraft’s works alive through the forties, fifties, and sixties, he published (via his own company, Arkham House) a whole slew of Lovecraft stories hitherto never seen. But on the downside, Derleth sought to replace Lovecraft’s uncaring, chaotic view of the universe with one much more in line with Judeo-Christian thinking.

On the side of "evil," Derleth placed the Great Old Ones, impossibly old and monstrous creatures who came from space and once ruled Earth but now sleep deep in the ocean or underground until "the stars are right" once again. And on the side of "good," Derleth placed the Elder Gods, a group of deities based largely on Greek and Egyptian mythology who would on occasion come to the aid of mankind. Along with the utterly alien and unknowable Outer Ones (such as Azathoth, who dwelled at the center of the universe), these beings were formed into a pantheon of sorts. It was completely antithetical to Lovecraft’s original vision of the Mythos, and a lot of fans tend to disparage Derleth for it, as well as Derleth’s practice of taking a fragment of a Lovecraft story, writing the bulk of it himself, and then claiming it as a collaboration. But I tend to cut Derleth a lot of slack for keeping the fires burning before Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos were "re-discovered" in the sixties and beyond.

Today, the Cthulhu Mythos has expanded to thousands of stories by hundreds of authors, dozens of film adaptations, and a vast number of works in other media, such as graphic novels and audio drama. Next time, we’ll be examining one of those "other media" works: the time when Lovecraft ended up in living rooms across America as an episode of the radio series Suspense. Until then, thanks for tuning in!

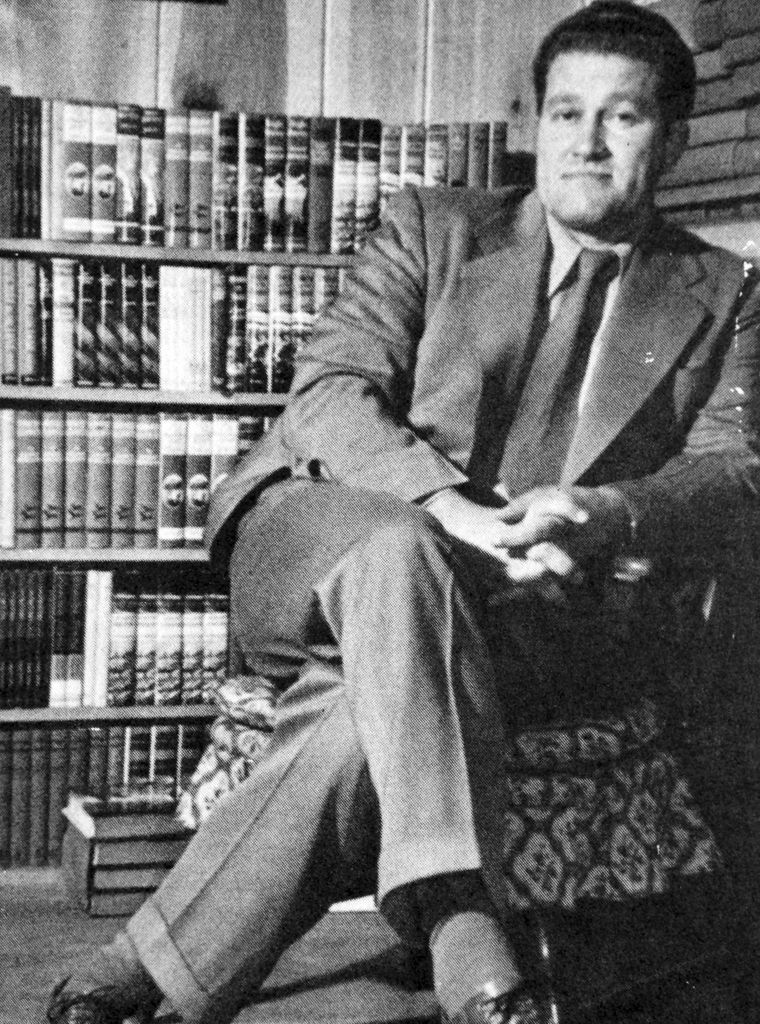

SUSPENSE writer, producer, and radio-drama aficionado John C. Alsedek shares the history of early radio and television and the impact it has made on the world of entertainment in his ongoing series for Flapper Press.

Comments